Each evening, sunset signals the begin of dinner for billions of wiggling sea monkeys living in the ocean. As these sea monkeys &mdash which are not basically monkeys but a type of shrimp &mdash swarm to the surface in one substantial, culminating force, they may possibly contribute as substantially energy to ocean currents as the wind and tides do, a new study reports.

Even although they're little, sea monkeys &mdash given the playful name mainly because their tail resembles a monkey's tail, but also known as brine shrimp (Artemia salina) &mdash may well contribute about a trillion watts, or a terawatt, of power to the surrounding ocean, churning the seas with the same power as the tides, the researchers said. A terawatt can light roughly ten billion 100-watt light bulbs.

Most people today recognize sea monkeys as common pets for youngsters and aquarium enthusiasts. Dehydrated sea-monkey eggs are quickly shipped and spring to life when they're placed in saltwater. Devotees can watch a group of brine shrimp hatch, develop and mate within weeks.

In the wild, brine shrimp migrate upward to the ocean's surface at twilight to feed on microscopic algae. At sunrise, they swim downward, away from menacing predators such as fish and birds.

A couple of brine shrimp swimming up and down don't have considerably influence on the ocean patterns. But with each other, multitudes of these tiny creatures generate sturdy currents that may perhaps have an effect on the circulation patterns of oceans about the globe, the researchers identified.

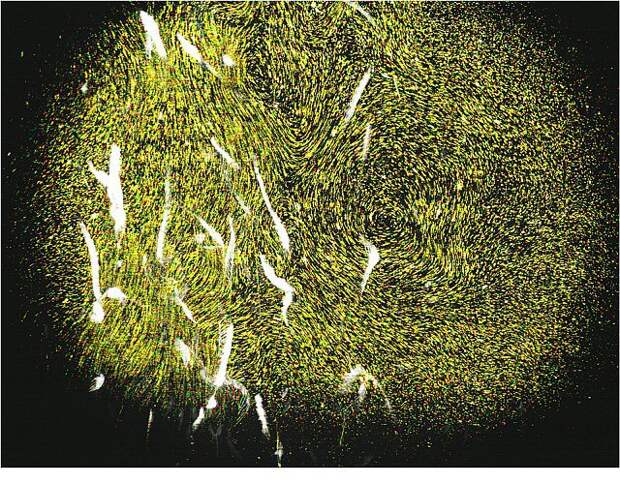

To get a much better sense of the brine shrimps' collective power, researchers examined them in a particular aquarium equipped with lasers.

(Brine shrimp tend to swim toward light, so using lasers would be a great way to herd them, the researchers reasoned.)A blue laser that rose from the bottom to the top of the tank triggered upward migration. At the same time, a green laser in the middle of the tank kept the brine shrimp centered in a group, equivalent to how they stick collectively in the ocean.

The shrimp have been tiny &mdash just .two inches (5 millimeters) extended &mdash but that didn't stop the researchers from measuring the swarm's communal existing. The group poured microscopic, silver-coated glass beads into the water and, with the assist of a higher-speed camera, recorded the altering direction of the water.

Every sea monkey has 11 pairs of legs that double as paddles. When two or extra of these creatures swim side by side, eddies they produce interact with bigger currents, which could adjust the ocean's circulation, the researchers mentioned.

"This investigation suggests a exceptional and previously unobserved two-way coupling between the biology and the physics of the ocean," study researcher John Dabiri, a professor of aeronautics and bioengineering at the California Institute of Technologies, stated in a statement. "The organisms in the ocean appear to have the capacity to influence their atmosphere by their collective swimming."

Ordinarily, researchers credit the wind and tides for producing currents that mix the ocean's salt, nutrients and heat. In contrast, this study suggests that microscopic animals also influence currents. In a study published in 2009 in the journal Nature, Dabiri and his colleagues proposed that sea creatures such as jellyfish mix ocean waters, and ventured that even smaller organisms could do the identical. This study presents evidence for their concept, at least in an aquarium environment.

In the future, the researchers program to use a tank with elevated water density at the bottom, which imitates real-life ocean situations. "If similar phenomena occur in the genuine ocean, it will mean that the biomass in the ocean can redistribute heat, salinity and nutrients," Dabiri said.

The study was published on the net Sept. 30 in the journal Physics of Fluids.